, or Embracing The Unfortunate!

Lemony Snicket has once more tread upon our screens to tell us of the woes of The Baudelaire Children. Inviting us to witness events already passed, though repeatedly warning us to look away, to continue upon our merry way, to do anything but hear a tale of loss and devastation. With each episode that slipped past I started to think about the allure of the series and its adaptions. There is something beguiling about the world The Baudelaire Children inhabit. We view it through a child-like imagination, where insides don’t match the outsides of houses, where it’s difficult to pinpoint geographic locations, as well as its place in time. It’s a world where certain oddity rules and where the fantastical and exciting come to life.

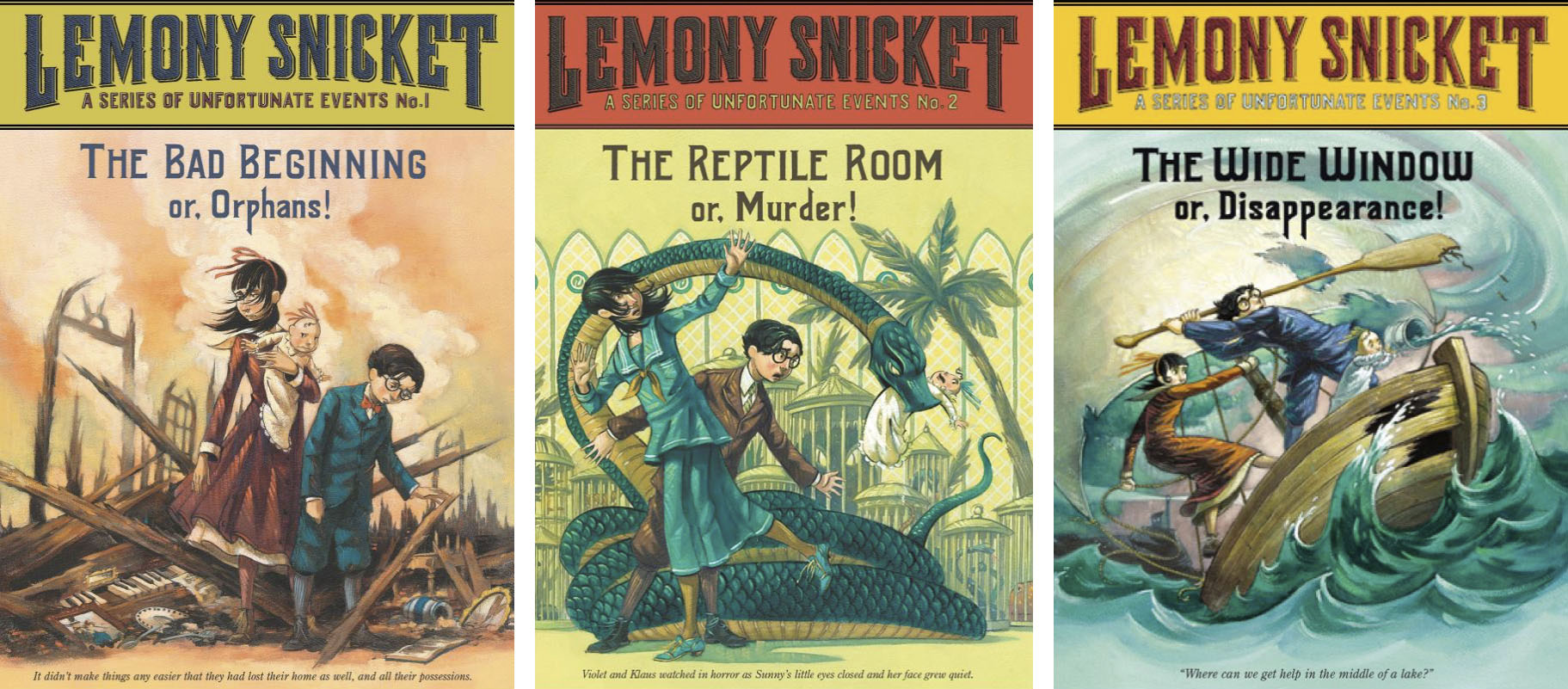

A Series of Unfortunate Events by Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) - The Bad Beginning first published in 1999, The Reptile Room first published in 1999, and The Wide Window first published in 2000 (Paperback Editions from 2007 by HarperCollins).

-

There is much that can be said on the stylistic choices both in the books, the show, and the film, and even more to be said on the overlapping genres in which the larger story Snicket tells is set. But neither style nor genre is something I want to touch upon in this piece—at least not in any great detail. I think what makes the tales of The Baudelaire Children so widely devoured is its embrace of the unfortunate. It shares with us that even well-meaning adults won’t always know what to do. That they’re flawed creatures. That they’re not always very brave, and that sometimes they can’t even be there for us at all. In an interview with Charlie Rose, Maurice Sendak said:

“Well, my feeling is you tell the truth as best you can, and the people who need the truth most are children, to defend themselves. To create a little quaint ghetto-land, otherwise known as kiddie-book-land, where you discreetly put in information which is totally useless to children, is something that bothers me a lot.”

It’s a delusion to pretend that these kinds of questions don’t make a home within the minds of children. Questions like: What if something horrible finds you? What if you find yourself lost? What if you’re hurt? What if you lose a loved one? Or even, in Sendak’s words:

“…they always say don’t run away and don’t turn your back. And don’t lie down flat. And I love—it’s from my childhood—how do you prevent dying? How do you prevent being eaten or mauled by a monster? I still worry about it.”

The Gashlycrumb Tinies by Edward Gorey (1963)

Which might sound completely illogical to those of us all grown and proper, but here’s what Sendak told Rose:

“I’ve been in the business for forty years, and for forty years I’ve heard from children, and their letters are so fierce.”

To which Rose replied:

“Fierce in what way?”

Well, I mean, they ask you such incredibly personal questions. You wonder ‘why are they asking me, and why aren’t they asking their parents?’ The answer simply is that they probably cannot ask their parents, so they ask the strange man who wrote the strange book. (…) I often don’t know the answer, but you just tell them that you don’t know the answer. What’s so touching is that they’re asking the question, and the questions frequently have to do with life and death and sex and sadness and morbidity, happiness, love. ‘Mama, papa, what’ll I do if they die? (…) Frank questions, pragmatic questions about life, you know, what will they do if they lose their parents? And so this, after forty years, tells me that these small people, their minds are teeming with serious questions about life, and then I think we do them an immense injustice when we patronise them in what we call children’s books, which is play time and cute time. I don’t want to generalise which, of course, I am, because there should be room for those books. They should have fun, too.”

Rose follows up by asking Sendak what the underlying theme is that runs through his books, to which Sendak replies:

“How does a kid get through an occasion when he or she is all by him or herself without the aid and assistance of an adult.”

“And the answer?”

“They make out as best they can.”

Through frustration, sadness, and longing The Baudelaire Children make out as best they can. They could break down and simply stop, they have enough reason to do so after all, but over and over they try. Never perfect. Never once truly out of danger. There is a great deal about the world Lemony Snicket creates that is unrealistic. I think, though, that the most important thing, the thing that makes his stories so enduring is that at its core it tells children that they can make out as best they can just as the Baudelaires do.

Rose, holding one of Sendak’s books up, ‘We Are in The Dumps with Jack and Guy’ asked Sendak:

“Now, some say this is a sad book and a painful book. Do you see it that way?”

To which Sendak replied:

“Oh, sure, yeah, it’s real life. It’s also a happy book because it has a happy ending despite all the odds. It also is a book about everyday life. How do you exclude sad from everyday life.”